Joyce Fetteroll has written something inspiring for unschoolers and mindful parents.

"Always say yes. Or some form of yes."

It's wonderful.

Lauren wrote:

Finding ways to say, "yes" when our first impulse might be to say "sorry, no," has been very helpful for me.Jenny Cyphers had a story in response:

I was at a park day the other day, only Margaux and I and one other mom and kids showed up. She has little kids, 1 and 3, she's on this list too. Her 1 yr old answers "yes" to just about everything. It's really really cute. We were talking about that, and the mom said that perhaps it's because she's always saying "yes", so that her little one copies that. I've seen little kids that will answer "no" to everything, and I got to say it's not nearly as cute as a little kid that says "yes" to everything. That affirmative answer is really powerful, even for really little ones that are just figuring it out!

At Joyce's site, she has softened her original advice:

Clare Kirkpatrick, responding to a new unschooling mom in 2015:

Consider saying 'yes' more often. Don't just say 'yes' without thought 'because some unschoolers told you to'. But *consider* saying 'yes' more often—in each instance in which you would normally say 'no', ask yourself 'why not yes?' And really pick apart (in as appropriate a time-frame as possible) why you would say 'no'. Is it because a 'yes' would feel frowned upon by others? Is it because you've always said 'no'? If you find yourself saying 'no' to the same things time and time again, then do a bit more deeper work on that issue. There may be something getting in your way you need to unpick— some cultural conditioning; some unhelpful and possibly untrue ideas about children.Don't put yourself under loads of pressure with this...just work on questioning your 'nos' and 'yesses' in more detail, more mindfully.

Clare

Agnès Lommez, not a homeschooling, but a French nutritionist or educator working on a government program to combat growing obesity (yes, even in France) was quoted in Time May 23, 2005 as saying:

The trick is never to tell the children no. Kids can and should eat chips, just not every day.

Pam Sorooshian wrote the following, in a discussion about children, parents saying "yes" when they can:

I went to New Mexico and Sandra picked me up at the airport. We then went to three grocery stores, one right after another, because Holly (who was maybe 4 or 5 at the time) was really wanting some plums and the first couple of stores we went to didn't have any. She wasn't being terribly demanding or whiny or anything—just saying, "Mommy I REALLY would love to have a plum." So we drove around—which was great because I got to see a bit of Albuquerque—and we got her some plums and she munched happily in the back seat while we talked. I was very impressed with Sandra's willingness to do this - most people would have thought it was MORE than enough to stop at even one grocery store because a child had a sudden urge to eat a plum. Most people would have just brushed off the child's urge (do we brush off our OWN urges like that?).

I thought then, and it has been confirmed for me on many occasions since, that when kids know that their parents are willing to go out of their own way to help them get what they want, that the kids end up usually more understanding and able to more easily accept it when parents don't give them what they want.This contradicts prevailing wisdom about "spoiling" kids though. And I know all of us have seen kids who do seem "spoiled" and whose parents appear to just give them everything on demand and the kids don't seem satisfied - nothing is ever enough and they whine and fuss and get demanding when they don't get what they want fast enough to suit them.

So—there is more to it—clearly. There is a respectfulness that develops between parent and child, over time, that is demonstrated by parents and expected of everybody in the family.

—Pam Sorooshian, 12/01

There is one word –

My favorite –

The very, very best.

It isn’t No or Maybe.

It’s Yes, Yes, Yes, Yes, YES!

“Yes, yes, you may,” and

“Yes, of course,” and

“Yes, please help yourself.”

And when I want a piece of cake,

“Why, yes. It’s on the shelf.”

Some candy? “Yes.”

A cookie? “Yes.”

A movie? “Yes, we’ll go.”

I love it when they say my word:

Yes, Yes, YES! (Not No.)

Here's a printable PDF: My Favorite Word

We know a lot of parents that say "no" a lot and belittle their children's dreams and ambitions and force their kids to focus on the parent's narrow view of success and what is "right."

I want my kids to feel empowered, so I empower them. I don't want their view of the world to be tainted by "can't", "shouldn't", "wouldn't", and the like. I want their world to be full of "yes I can," I shall find a way to do what I want to do with my parent's blessing and help.

So many parents set their kids up where the kids have to defy their parents to get what they want in life. That is such a huge obstacle and burden for a young person, almost to the point of self defeating. Some young people don't have that strength of character or drive to jump that hurdle and so, stay stuck in that world.

Amy/arcarpenter wrote:

Two recent examples from our lives about saying yes, in this case to a very young child:

Example 1:

(My response to a discussion on another list about punishment.)

Saying yes doesn't mean that I ignore my needs and limits, or that I don't keep my children safe, or that they don't learn how to treat people well. We talk about all these things, and I model respect, and we often come up with solutions together. I'm not nearly perfect at it yet, but I really don't punish anymore, and I'm always trying to work my way toward "Yes, and how can I help?"

Even with Riley, my nearly 2 y.o., who doesn't talk yet — he very

clearly makes his wishes known , and he is more and more able to

model his behavior on what the big people in his life do. This is not

a compliant, "obedient" type of kid at all. But he can work towards

solutions (in his own nonverbal way) because I'm honest with him, in

how I treat him — I always try to find a way to say yes to what he

wants.

For instance, today he really wanted to play with the raw eggs — he didn't understand the difference between the hardboiled ones I usually give him and the raw ones in the fridge — so I brought one raw egg up to the bathtub, stripped him to his diaper, and let him play with it there. Boy, was he surprised when it broke! It was fun to watch.

So he's starting to understand that if he's trying to get to something and I can't seem to find a way to let him, it's because even the big people don't do that, and there's a good reason.

That's very different from when adults get to do things but then tell the little ones that *they* can't or that "we don't do that," — a hypocrisy that children see from very early on, which hurts and confuses them. Children in those families will be looking for ways to get beyond the artificial limits because they are trying to figure out the world around them — they have a dead serious need to get that information.

Example 2:

(My response to a discussion on another list about young children who "don't listen" in dangerous situations, like running in the street.)

I think if you watched my younger son (Riley, almost 2 y.o.), you would probably also say that he "doesn't listen." He is very curious and active, and he used to run into the street.

Here's how I've worked with teaching him not to run into the street — I let him go into the street. Sounds crazy, but let me explain.

We live on a cul-de-sac with little traffic. If we didn't live on a calm street, I would probably take my son to a calm street and let him play in it. I stand by him the entire time, and if a car comes, I pick him up and take him to the sidewalk until the car is gone. I tell him about the car while I'm holding him (and sometimes he is struggling), and then I point out why it's safe to go back into the street when the car is gone. Then I put him down and let him walk back to the street.

If we walk by a parked car, or if we play with our cars in our driveway, I point out where the windows are and how low Riley is compared to the windows, how the drivers can't see him. It's just part of the talking and sharing information that we always do around here.

Riley almost never goes into the street anymore. He knows what it's like, and he's learning how the big people handle the street — and that's all he really wanted to know in the first place. I'm also careful about the words I use with him, saying "go to the sidewalk, please" instead of "no" or "don't go in the street."

When a ball rolls into the street, he chases it until the end of the driveway and stops. When my husband or I go to get the ball, Riley sometimes follows us and sometimes doesn't. If it's not safe for him to follow us, I tell him to stay on the sidewalk. If he didn't stay, I would stay with him until the danger had passed. But he almost always stays by now.

The last time that he and I took a stroll on the sidewalk, he was interested in crossing the street, and he was willing to hold my hand while he did it, and he seemed to understand that we needed to walk straight across to get to the other side (as opposed to staying in the street a long time).

He knows about the street at a younger age than my other son did (and my other son is the one that everyone said was a "good listener," meaning he has a calmer, more observant personality that people often think is "obedience."). With my older son, I didn't let him go in the street and always said "no" without thinking about whether or not there was a way to say yes.

My explanation for this: once the power struggle stopped, the learning could begin.

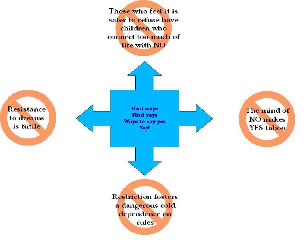

Click to enlarge and read about this Very useful graphic by Katherine Anderson.

Jenny Cyphers, about bananas:

My kids are older, 8 and 16, and when they figured out how to open a banana like a monkey, they opened them all up because it was fun to do! What they didn't eat, I put in the freezer for making smoothies later. The curious exploration of the world, by my kids, has led to all kinds of creative thinking and problem solving for me too, which keeps my own old brain from being stuck!I love that about unschooling! I know plenty of parents that would never have allowed their children to open up all the bananas because it would have been wasteful! What really would have been wasted, was the opportunity to explore and learn! When others have said, especially Sandra, that learning is more important, or that learning comes first, this is exactly how I have come to understand it. That "YES" we can open up all the bananas and learn how monkeys do it, and that none of them will go to waste!

Robyn Coburn wrote, "Something that comes up a lot is the concept of safety, or the idea of saying "no" when something is unsafe. I wrote this fairly recently:"

One of the processes that I have noticed in our life, and also in the postings of others, is that the definition of "safe" has definitely moved towards the liberal. I find I have to re-examine every time what is safe. There are times when people visiting our home get agitated because Jayn is climbing on furniture in way that makes them concerned. I have to reassure them that she is very balanced and confident. (Jayn's maternal grandfather was a tightrope walker in a circus—I think she is showing signs of inheriting his abilities—skipping a generation.)There are ways that I change my response to "unsafe" mental alarm bells, rather than making the default position "Jayn must stop or change her activities":

I seems to me it is about saying "yes" through my actions, as well as my words.

- I reorder the environment, putting pillows, moving breakables etc.

- I re-examine the environment and action, rather than acting on a knee jerk reaction. The example that comes to mind is "running around the pool". Our pool surround is very old concrete, so pitted that it just does not become slippery. In addition experience reminds me that Jayn is cautious and has never fallen while running in the wet. When we visit another pool, I do a check to test the slipperiness of the area, and share my findings with Jayn.

- I ask myself what I would be depriving Jayn of by making an arbitrary (or my-comfort-based) decision on her behalf. It becomes risk assessment. How much would she realistically be hurt by falling onto her butt, versus the emotional hurt and stress on our relationship by me not trusting her or diminishing her self-confidence.

- I show Jayn the safe way of accomplishing the action—like holding a plug by the plastic and not touching the metal prongs.

Robyn L. Coburn

Sandra Dodd (to Robyn's post above):

The risk assessment point is good.This photo was taken of Kirby and his dad, the day of the story below Click it to see some other costumes.

The writing is mine ("Ælflæd" is Sandra).I remember one day vividly when Kirby was one. Probably 16 or 17 months old, and walking well. We were at an SCA tournament near Colorado Springs, and he was little enough to be picking other people's stuff up without asking (he wasn't big enough to ask or know "other people's stuff"). He walked up holding a steel and leather gauntlet. I asked him where he got it, but asked him nicely in the same kind of interested way I would've if it was a cool rock or a flower rather than stolen armor. 🙂 He very happily led me to the place. I apologized to the guy (who hadn't yet noticed it missing) and asked if maybe he had anything that wasn't his. There was something there, a roll of duct tape or something. So I thanked him and picked that up and went to the next interesting pile of stuff and asked if it was theirs. It was. Did they have something that wasn't theirs? They did.

So Kirby had cross-pollinated a whole row of stuff in wandering among people who knew who he was and knew his dad and I were within eyesight.

Nobody told him he was a bad boy. Everyone got their stuff back. He got to look at and touch some cool things, and that was fine.

At one point that afternoon he fell down and cried. He had tripped on a string that was set up six or eight eight inches off the ground between stakes (sagging between stakes) to show people how close was too close to put tents and piles of armor. The adults were walking over it easily and had seen those little barriers before. Kirby tripped and fell. After I made sure he was okay and dusted him off, I took him back over and showed him the string and helped him practice stepping over it, and pointed out how the string went all the way around those places, and where the other people were walking where there wasn't string. "That's all," I remember telling him. It was only a string. Not danger, not malice, not his failure to walk.

A guy from Santa Fe I knew, thirtiesh, nice guy, was watching us and listening. He came over and said with tears in his eyes that I was a really good mom and he wouldn't have thought to explain to someone that age what had happened. Then he told me something he had never told me or any of us in that group as far as I know. He had a daughter, somewhere, 14 years old. He had gotten his girlfriend pregnant when they were sixteen or so, and the girl didn't want him to stick around and be the father. So he said he always watched parents and thought about what he would do, how he might have been, as a father. He had spent years being ashamed and sad.

Years passed. He married and has children (I haven't met them, they're in another state). I feel good about that, and he's probably a better dad than he would've been if he hadn't hung around with us for a few years.

And because of his story about having a daughter he didn't know and had never parented, I was able to calmly and truthfully tell my boys that one reason they need to be extremely careful about unintended pregancy is that if they get a girl pregnant, it's not their call whether she has the baby or not, and it's not their call whether they get to be the daddies or not. They WOULD be a father, and regardless of their desires or intentions, they might end up being absent or bad fathers, because the baby was the mother's baby to decide about.

It's another risk assessment situation.

- Yes, teenagers sometimes have sex, but do it safely.

- Yes, there are places more dangerous to walk than others, so do it safely.

- Yes, you have something that doesn't belong to you, yes it's okay to pick things up, and yes, let's go take it back.

Sandra

On the Always Learning list in June, 2007, a mom came back after ten years and reported on changes in her unschooling life:

Title Art by Holly Dodd